The Pockets of Shaw

Mark Whitty

This material is copyright to a number of sources, including Dr John Shaw, Mr Andrew Shaw , The Bulletin of OMR&RCA Ltd., and WOOMB International Ltd.,

by whose kind permissions it is presented here for personal private study.

Wilfred Shaw

Wilfred Shaw (12 December 1897 to 9 December1953) was a British gynaecologist, pathologist and author of numerous textbooks and papers on gynaecological subjects. Born in Birmingham. He studied medicine at St. John’s College Cambridge, and at St Bartholomew’s Hospital, London, qualifying in 1921; FRCS1923; MD1928; FRCOG1932.

Postgraduate studies in Dublin, Vienna, and other centres in Europe.

Career: after various junior appointments, he became Resident Assistant Physician Accoucheur at Barts 1926-31; Surgeon in charge of the Gynaecological and Obstetrical Department at Barts 1946-53. In the Williamson Laboratory at Barts he studied ovarian and uterine physiology and pathology.

He developed new operations for stress incontinence and pelvic floor prolapse repair.

His awards include: Raymond Horton-Smith Prize, Cambridge 1929; Jacksonian Prize, RCS 1931; Arnott Demonstrator, RCS 1933.

Publications: Textbook of Gynaecology, 1936 (15th edition 2010: Elsevier: Padubidri & Daftary); Textbook of Midwifery, 1943; Textbook for Midwives, 1948; Textbook of Operative Gynaecology, 1954 (7th edition 2013; Elsevier: Setchell, Shepherd, Hudson); numerous papers and reviews.

A particular focus of his work was the refined and classical study of normal vaginal anatomy, for the purpose of restorative surgery. He identified the anatomical structures which became known through Professor Erik Odeblad’s work as “The Pockets of Shaw”. These were first internationally recognised in 1959 as “The Folds of Shaw” in Professor Kermit Krantz’s opening lecture of the New York Academy of Sciences’ International Symposium on “The Vagina”. Professor Odeblad also spoke at that Symposium.

Shaw would have greatly appreciated Odeblad’s work on the cervix, and also his gradual elucidation, over the succeeding decades, of the function of the Pockets in the context of female physiology and fertility.

Sample references for the Pockets:

- Lancet 18-2-1950, 306

- Krantz, K. E.: The Gross and Microscopic Anatomy of the Vagina. Annals New York Academy of Sciences 83, 89-104 (1959).

_____________________________________________________________________________________________

Anatomy

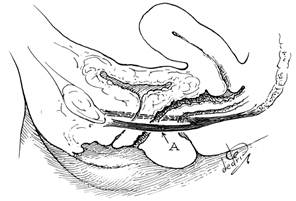

British Medical Journal 12-4-1947, No. 4501, pages 477-482; “A Study of the anatomy of the vagina, with special reference to vaginal operations”.

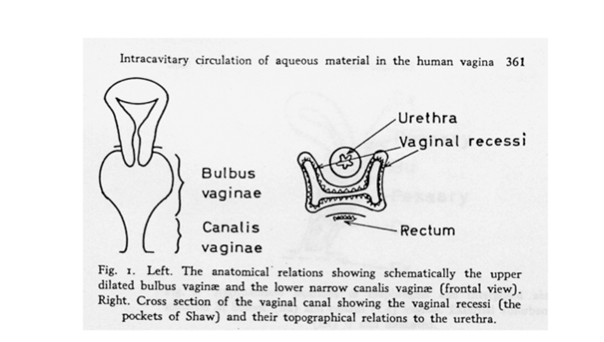

“A specialised fold of skin can be distinguished which passes from the lateral vaginal wall deep to the hymen to the vicinity of the submeatal sulcus. This fold is small and is best referred to as the oblique vaginal fold. Its significance is unknown, but below and lateral to it is a recess, lying lateral to the urethra, which is best referred to as the paraurethral recess.”

Annals of the New York Acad. of Sciences, Vol. 83, Art. 2, pp 77-358; 18/11/1959:

International Symposium 10-11 April 1959.

Dr Kermit Krantz; “The Gross and Microscopic Anatomy of the Vagina”;

‘In the area of the urethra this ridge becomes more prominent and is termed the urethral carina. In the region of the origin of the urethral carina a deep lateral groove and fold are present. This, in conjunction with a similar fold less prominent in the posterior vaginal wall at the upper level of the levator ani, has become known as the fold of Shaw.’

Krantz

Krantz

Odeblad

Two patterns, two points of change, and four rules.

Physiology

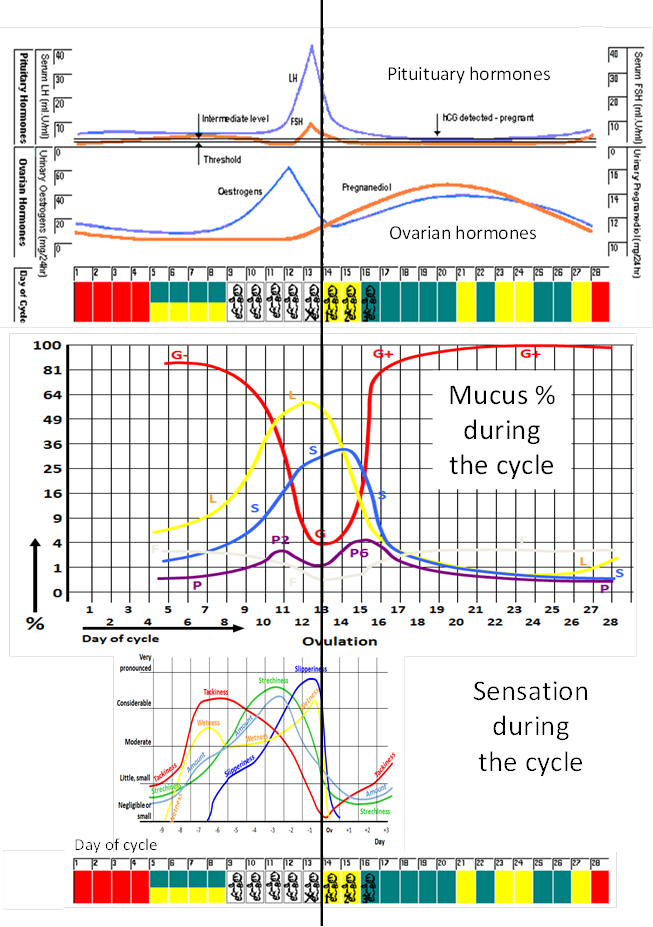

The anatomy of the Pockets of Shaw is of little use without its physiology; its hormonal function. The Pockets resorb water content under the dominance of progesterone. This provided the explanation of the First and Second Points of Change; the First has been called the oestrogen change, from the unchanging Basic Infertile Pattern to the changing, developing potentially fertile pattern leading to the Peak. The second has been called the progesterone change.

The two patterns and the two points of change are identified by refined but simply learned observation that is “tuning in” to the sensation at the vulva during the day, and the autonomous but consistent recording of the days’ observation each evening.

The four Rules cater for each stage of a woman’s reproductive lifespan and the variants that occur within these. There are three Early Day Rules and one Peak Rule. (1) no intercourse during heavy menstrual bleeding (because the start of mucus discharge could be masked by the bleeding) (2) alternate evenings are available for intercourse when the BIP has been identified (by evening the woman knows if there is a change from the BIP; the seminal and other fluids gradually disappear the day after intercourse, revealing whether the BIP has continued that day) (3) Intercourse is avoided if there is an interruption of the BIP, and may be resumed from the 4th evening after the return of the BIP if there was no Peak. Peak Rule; Intercourse is “available” any time from the beginning of the 4th day after Peak until the end of the cycle. These rules can be used to avoid and to achieve pregnancy as well as to monitor reproductive health.

For further information visit http://www.thebillingsovulationmethod.org